In my post about the Battle of Waterloo, I tell the story of how the Rothschild family got into “the big leagues” financially, by funding both sides in the Battle of Waterloo, and gaining personally from the information they were privy to more than twenty-four hours before anyone else.

Here I’ll explore how usury ended up in the United States in the 1800s and in further posts on this site, how it became the basis for the Federal Reserve. It’s a story of intrigue, deception, ruthlessness, and greed.

The Monster Travels to the “New World”

When the American colonies were originally settled, beginning in the early 1600s, they were founded under mercantilism. The mercantile system of the British Empire stipulated that commerce and growth within these early settlements was for the enrichment of Britain. Trade by the colonies with other empires was forbidden, taxation would originate from the motherland, and money would be created in Britain and “loaned” to the colonies with interest. The Royal Navy, which dominated the seas, was easily able to both protect its merchants and police international trade.

When the American colonies were originally settled, beginning in the early 1600s, they were founded under mercantilism. The mercantile system of the British Empire stipulated that commerce and growth within these early settlements was for the enrichment of Britain. Trade by the colonies with other empires was forbidden, taxation would originate from the motherland, and money would be created in Britain and “loaned” to the colonies with interest. The Royal Navy, which dominated the seas, was easily able to both protect its merchants and police international trade.

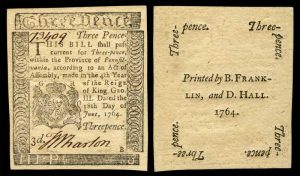

In 1691, Massachusetts began to create its own money, called Colonial Scrip. It resulted in controlled growth, an inflation-free environment, and no taxes. Other colonies followed with slightly different models and less success at keeping inflation at bay.

It was not until three years later that the Bank of England was founded, in 1694. It was founded on the principle of fractional reserve banking and compounding interest—the model for the banking system we have worldwide today.

In 1763, Benjamin Franklin, from Pennsylvania, visited London. He was apparently shocked to see the poverty and squalid conditions of most of the population. Asked to explain how the colonies were doing so well, he replied:

“In the colonies, we issue our own money. It is called Colonial Scrip. We issue it in proportion to the demands of trade and industry to make the products pass easily from the producers to the consumers. In this manner, creating for ourselves our own money, we control its purchasing power, and we have no interest to pay anyone.” Benjamin Franklin, A History of Central Banking, Stephen Milford Goodson.

That was a mistake—for Ben to be so open about their monetary successes.

Franklin’s way of creating money for the colonies was viciously opposed by English bankers. After all, the entrenched method in Britain was to borrow money from bankers at interest. A year later, King George III issued a bill that severely restricted the right of the colonies to issue their own currency.

It didn’t take long for the economy of the colonies to collapse and within a year, half the population were unemployed and destitute. They had been forced to pay taxes to England in silver or gold, and since they had no mines, they went into debt to do so. This created a deflationary environment and it was the primary cause of the American Revolution which, of course, led to a complete break from England in 1776.

The First American Currency War

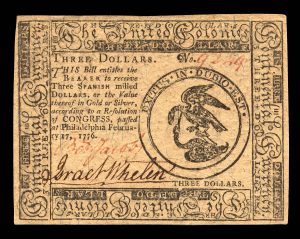

The colonials now found themselves at war with no money with which to pay for it. A Continental Congress met and decided to issue $200 million in Continental Currency (or scrip). It certainly spurred the economy, but flooding the marketplace with currency only works for a while; it ultimately leads to inflation, which severely lowers the value of the money in circulation.

“By the end of the war, the scrip had been devalued so much that it was essentially worthless; but it still evoked the wonder and admiration of foreign observers, because it allowed the colonists to do something they had never done before. They succeeded in financing the war against a major power, with virtually no “hard” currency of their own; and they did it without taxing the people.” —Ellen Brown, Web of Debt

“Without taxing the people” is a misnomer, because inflation is a tax. Your money reduces in value so, in fact, prices of assets, products, and services rise, GDP rises, but your salary doesn’t increase, and the cost of living goes up. Eventually, to retain your lifestyle, you end up in debt.

Just to “hurry up” the inflationary effect, the British Government weighed in with one of their favourite “old tricks”:

“The Bank of England quickly responded. Hundreds of workmen were recruited and soon millions of dollars worth of counterfeit banknotes were rolling off the printing presses and being shipped to New York. The continental dollar retained much of its purchasing power during the first two years of its issuance, but once the English counterfeit banknotes started to increase in circulation, its value so soon fell away and by 1781, was worth only 2.5 cents.”—A History of Central Banking, Stephen Mitford Goodson

From the destruction of the Continental dollar came the expression, “Not worth a Continental.”

The English had a habit of using counterfeiting as a weapon to attack their enemies. They did the same thing to France during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-97) with the assignat, which was the currency of the French Revolution. They flooded the country with counterfeit paper fiat money. This was a key reason for Napoleon taking complete control of the banking system when he came to power.

The First American Banks—Private and Lucrative

Even before the colonies had drafted a constitution, they had their first bank (The Bank of North America, founded in 1781, during the war), modelled after the Bank of England. That meant it was based on fractional reserve banking with fiat money. The private bank was riddled with fraud and, because of this, its charter was allowed to expire after two years, in 1783.

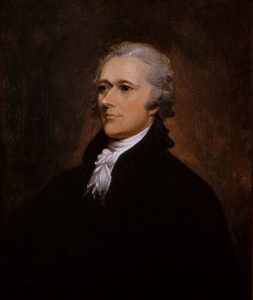

The next bank idea came from Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton. His plan was to found a private bank that would create money and lend most of it to the government. It would keep the ability to create money out of the hands of politicians. Thomas Jefferson vehemently opposed the plan and fought to the point that the rift ended up creating the two political parties in existence today. Hamilton won the argument and in 1791, the First Bank of the United States was established with a twenty year mandate.

The argument of private bankers for keeping money creation away from governments is that they will cause hyperinflation. However, that’s been disproven over and over again.

The First Bank of the United States didn’t turn out much better than the Bank of North America. The Rothschild family ended up being the major investor which gave them power both financially and politically. The bank’s main purpose was to lend money to the government at interest and within the first five years, it had helped inflate the economy by 42%.

“By the end of 1795, the Bank had lent $6 million to government or 60% of its capital. As the bank was allegedly concerned about the stability of government finances, it demanded partial repayment of this loan. The government did not have the funds available and was therefore forced to sell its shareholding in the bank between the years 1796 and 1802. By means of this cunning ruse , the bank became 100% privately owned, of which 75% of the shares were held by foreigners.”—A History of Central Banking, Stephen Milford Goodson

In 1811, the bank’s charter came up for renewal. Former president Thomas Jefferson violently opposed renewal. It was a hard-fought battle that went on for days in Congress. It was close: Renewal was defeated by one vote in the House, and one vote in the Senate.

“When the principal shareholder of the First Bank of the United States, Mayer Amschel Rothschild heard about the deep dissension regarding a renewal of the bank’s charter, he flew into a rage and declared that, “Either the application for renewal of the charter is granted, or the United States will find itself involved in a most disastrous war.”—A History of Central Banking, Stephen Milford Goodson

“Let me issue and control a nation’s money, and I care not

who writes the laws”—Amschel Rothschild

In 1809, Spencer Perceval became Prime Minister of England. During this period, England was in a war with France, both sides financed, of course, by the Rothschilds. After the vote in the US to decommission the bank, Nathan Rothschild put tremendous pressure on Perceval to declare war on the US. Perceval was already tied up financially in the war with France and refused.

On May 11, 1812, Perceval arrived at the House of Commons for a debate and vote. He was assassinated in the lobby by John Bellingham, with a shady past and possible ties to the Rothschilds. Within the year, the US and Britain were at war—the War of 1812—a war which was completely unnecessary.

The Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was set up in 1816 and it was 80% privately owned. In 1822, President James Monroe appointed Nicholas Biddle president of the bank. Biddle was the point man to James de Rothschild, who was the bank’s principal investor.

“The charter required the Bank to raise a minimum of $7 million dollars in specie (gold and silver), but even in its second year of operation, its specie never rose above $2.5 million. Once again, the monetary and political scientists had carved out their profitable pieces, and the gullible taxpayer, his head filled with sweet visions of “banking reform,” was left to pick up the tab.”—The Creature from Jekyll Island, G. Edward Griffin

America was about to be introduced to her first boom-bust cycle.

“In 1818, the Bank suddenly began to tighten its requirements for new loans and to call in as many of the old loans as possible. The contraction of the money supply was justified to the public then exactly as it is justified today. It was necessary, they said, ‘to put the brakes on inflation.’ The fact that this was the same inflation the Bank had helped to create in the first place, seems to of gone unnoticed.”—Creature from Jekyll Island, G. Edward Griffin

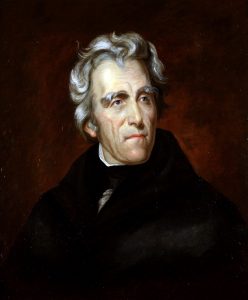

The depression of 1819-21, in which the bank was able to buy up assets at depressed prices raised the ire of Andrew Jackson, head of the Democratic party. In his election campaign of 1832 for President, he declared that “the monster must perish” and ran his entire campaign on “Andrew Jackson – No Bank.”

“Notwithstanding a failed assassination attempt on January 30, 1835 by a presumed Rothschild agent, Richard Lawrence; when a 20 year charter of the Second Bank of the United States came up for renewal in 1836, Jackson collapsed the bank by withdrawing all government deposits. He promptly repaid the National Debt in its entirety, leaving a surplus of 50 million in the treasury.”—A History of Central Banking, Stephen Milford Goodson

In 1837, the Second Bank of the United States was no more. Jackson had beaten the bank. He had also survived an assassination attempt. Luckily, both the assassin’s shots missed him. He was one of few to tangle with the banking cabal and live to tell about it.

America was in the middle of a boom, due to the fact that the Bank had increased the money supply through loans by 84% through fractional reserve banking (in other words, debt). But when the Bank disappeared, the money disappeared, because that money wasn’t backed by anything. It was called the Panic of 1837; deflation roared in, as it always does in these situations.

Men were put out of work, homes and savings were lost. Many other banks also went bankrupt, with their owners walking away with what was left. The depositor was left holding the empty bag, as usual. Thirty-two Massachusetts banks collapsed between 1837 and 1844.

For the next 77 years, the economy got along without a central bank.

President Lincoln and Greenbacks

The American Civil War was a clash between the economic interests of the North and South. The issue of slavery was raised as a way to get people to fight, but was secondary to the main issue of the economy.

In 1861, the expenses of the federal government were $67 million. After the first year of combat, they were $475 million. Taxes would only cover about 11% and government war bonds would cover about half the needed amount.

In 1862, Congress authorized the Treasury to print $150 million worth of bills of credit and put them into circulation as money to pay government expenses. They were printed with green ink and became known as “greenbacks.” By the end of the war, $432 million in greenbacks had been printed.

The impetus for the creation of fiat money (greenbacks) to pay for the cost of the civil war originated in Congress, and President Abraham Lincoln was a very enthusiastic supporter:

“It would appear that Lincoln objected to having the government pay interest to the banks for money they create out of nothing when the government can create money out of nothing just as easily and not pay interest on it.”—The Creature from Jekyll Island, G. Edward Griffin

The National Banking Act

On February, 25, 1963, Congress passed the National Bank Act, which established a system of nationally-chartered banks. This was a whole new system that was to set the country on a course to perpetual debt.

The system was based on the government issuing bonds. The national bank would pay for these bonds, but they didn’t keep the bonds; they gave them back to the Treasury. The Treasury then exchanged the bonds for an equal amount of US Bank Notes with the bank’s name on them. So the banks still owned the bonds and received interest on them, but also had the money from the government that they could then lend out at interest.

The banks were required to keep about 12% on hand as reserves to prevent a bank run (which of course, would happen anyway, if everyone wanted their money at the same time). This then, was just a slight variation on the exact same system we have today: fractional reserve banking.

The way the money got into the economy was through loans. So, as I explained in my post on how banks create money out of nothing, it would put the country into perpetual debt:

“Rarely has economic circumstance managed more successfully to confound the most prudent in economic foresight. In numerous years following the war the federal government ran and heavy surplus. It could not pay off its debt, retire its securities, because to do so met there would be no bonds to back the national bank notes. To pay off the debt was to destroy the money supply.”—John Kenneth Galbraith, The Creature from Jekyll Island, G. Edward Griffin

While all this went on, in the background lurked the Rothschilds and other central-banker-types. They would await their opportunity, which would come around again in 1913. They were obviously upset not to have a piece of the American money pie.

“Lincoln’s defiance of Lionel de Rothschild and his uncle James resulted in his assassination on the night of April 15, 1965 by John Wilkes Booth (real name Botha) at the behest of the Rothschilds’ local agent named Rothberg.”—A History of Central Banking, Stephen Milford Goodson

President Garfield Speaks the Truth

The bank runs of the second half of the 19th century made President James Garfield so angry that he issued a statement on March 4, 1881:

“Whosoever controls the volume of money in any country is absolute master of all industry and commerce … And when you realize that the entire system is very easily controlled, one way or another, by a few powerful men at the top, you will not have to be told how periods of inflation and depression originate.”—A History of Central Banking, Stephen Milford Goodson

Two weeks after his made that statement, President Garfield was gunned down by Charles J. Guiteau, who apparently was angry at not having received a diplomatic posting.

“At his trial, the hidden hand of Rothschild was revealed when Guiteau claimed that ‘important men in Europe put him up to the task, and had promised to protect him if he were caught.'”—A History of Central Banking, Stephen Milford Goodson

The Bottom Line

It should be relatively clear now that this cabal of central bankers will stop at nothing to gain control of the economy of countries around the world through usury. Under the auspices of creating financial stability worldwide they contract with governments to supply the money for their citizens, money they create out of thin air, and charge compounding interest for that privilege.

It should be relatively clear now that this cabal of central bankers will stop at nothing to gain control of the economy of countries around the world through usury. Under the auspices of creating financial stability worldwide they contract with governments to supply the money for their citizens, money they create out of thin air, and charge compounding interest for that privilege.

In fact, if pressed, any central banker would have to admit that they have no real need to get paid back the principle of the loan, but rather that they are happy to have the principle sit idle, as long as they are paid the interest, which is their income.

Since the principle equals the amount of debt created at the time of the loan, it is really just an accounting entry (the asset equals the liability). When the principle is paid back, both the “money” and the debt disappear from the double entry accounting sheet at the same time. The money disappears as quickly as it was created. But since the debt side of the equation is recorded on the books as an asset, the bank loses the “value” on the asset side of the equation if the debt is repaid. This is without a doubt accounting “trickery.” It’s simply fraud.

“Fraud,” defined in Black’s Law Dictionary is “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”

But what’s worse is that by creating loans, which create the flow of money into the economy, they create inflation. Creating loans is their job and they’re paid handsomely through interest to do that job. However, inflation is the obvious by-product, and that’s back for the citizens of a country is the long term, because it debases the money (decreases its value).

Banks are incentivized to create as many loans as they can, each one increasing their income (through the interest paid to them) with no cost (other than the labour to keep the books) and no downside … until the economy starts to suffer, the loans start to default, banks start to restrict credit, which in turn reduces the money in the economy.

A contributing factor is that when inflation reaches a certain level, the money of a society has been debased to such an extent that it substantially raises the cost of living, major purchases become unaffordable, and the economy starts to contract. We move into deflation, banks pull loans, and people lose their assets and their livelihoods. Banks get baled out and the taxpayers foot the bill. What a system we’ve created!

In Canada, we’re suing our government to get back our public central bank, the Bank of Canada, which has a contract with the Bank of International Settlements (yes, the same cabal of banksters) to create our money for us (from nothing) and charge us interest for it. For decades, we used to do that for ourselves. The story is a similar one all over the world.

Today we’ve created the largest inflationary bubble in history. The downside, of course, will be a deflationary spiral so devastating to be virtually unimaginable by the almost anyone on Earth. It’s a man-made cycle that has repeated over and over again with some amount of regularity, throughout history.

Thanks Peter… Watching you.. LOL [wink]….nick